Or What I Learned About Writing by Winning the Moth StorySlam(s)

The Moth, a nonprofit organization, preserves and shares true personal stories, told live. Stories are collected for radio and podcast through curated performances and StorySlams—open mic opportunities held all over the world. Several years ago, I puffed up enough courage to go to my first StorySLAM in Seattle and put my name in the hat. My name has now been drawn eight times, and four out of four of my last visits, I won.

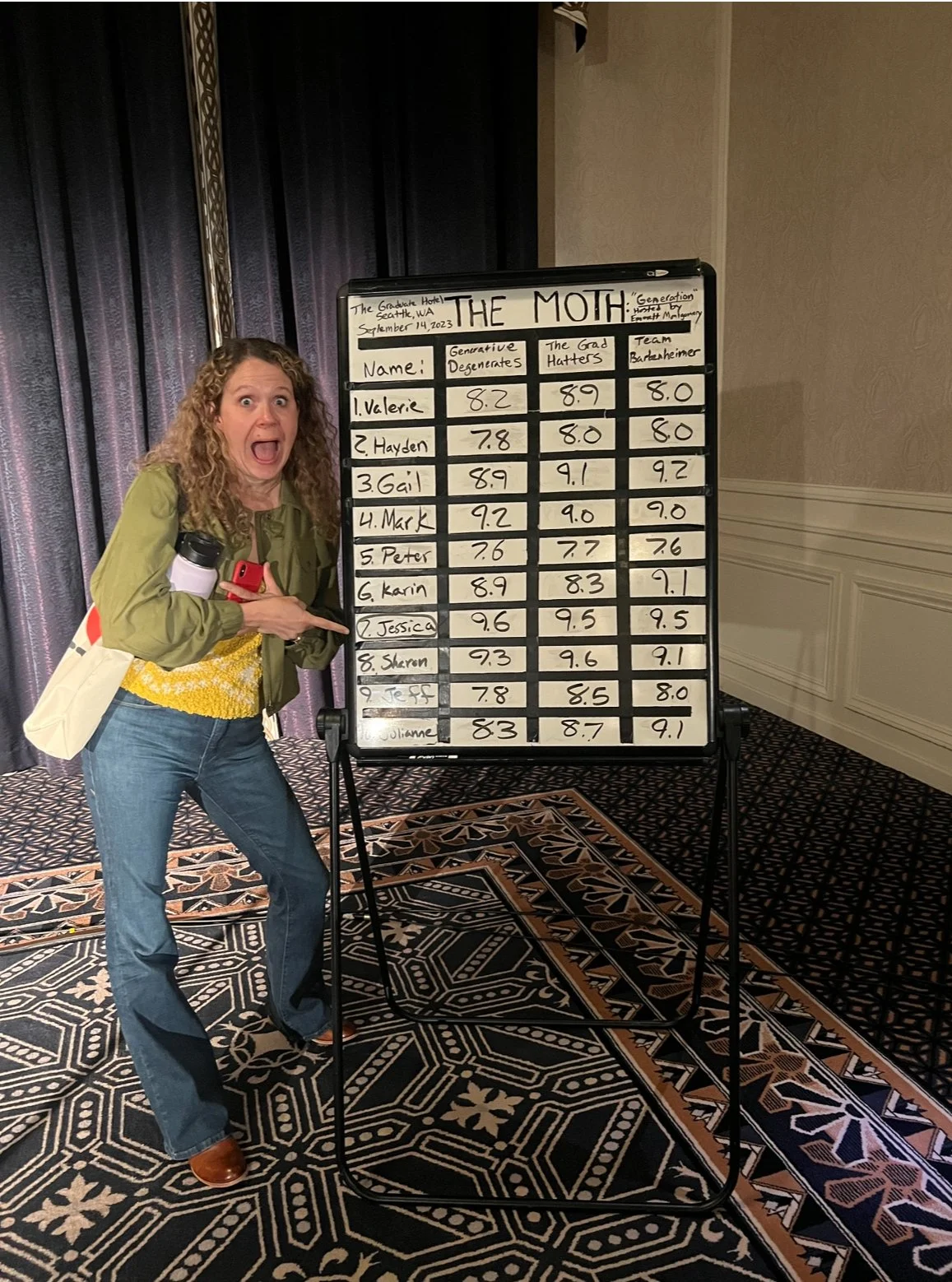

Here are the rules, in my own words: tell a story that is yours alone, do not use notes, do not exceed five minutes. Three randomly selected judging teams score each storyteller on elements like length, story flow, and adherence to the night’s theme (things like “First Impressions” or “Mama Rules”). At the end of the night, a winner is crowned and earns the privilege of participating in a GrandSLAM—a contest of ten winners in a much bigger venue. At a StorySLAM, all the stories are recorded and may be used for the radio hour or podcast. One of my earlier stories was featured on the podcast, a gratifying result.

Five minutes is not a long time to win over an audience, but it is long enough to make them yawn or cringe. The StorySLAM crowds are supportive and warm every time. I want to repay my listeners’ kindness by providing an excellent, engaging, empathetic experience. The feeling of uniting two hundred people in a common mood, inviting strangers to my heart intoxicates me. I can sail through a depressed, dark Pacific Northwest winter a little more smoothly on a StorySlam performance high.

Here are my four secret ingredients: vulnerability, laughter, detail only I can share, and a lump in the throat.

In the StorySLAM context, connection is created by vulnerability. Everyone there is aware of the courage required to stand and tell your life to strangers, to not know whether you’ll be selected to speak until three minutes before you go on! They are ready to support but can smell a fake, over-rehearsed, or miserly telling from a mile away. But, divulging the real feeling behind the story, the embarrassing details, or the cost of the events in a story creates an immediate mood of camaraderie. It’s the same with personal nonfiction writing: even if a reader has never shared your exact experience, they can quickly tell if you are trustworthy and truthful.

Laughter does more than just give everyone a free, ten second abdominal work-out—it promotes production of happiness hormones! I’m not a neuroscientist but know from experience that a room full of laughing people is a room full of people experiencing pleasure from dopamine and a sense of unity from my favorite hormone, oxytocin. A chuckling audience—or reader—is one with a brain feeling safe, peaceful, joyful, and receptive. I tell stories about physical and emotional wounds, harrowing betrayals, and loss. Revealing my inner life to the audience is scary, but it’s a gift very worth giving. Every time, I try to provide at least one hearty, collective laugh. It puts me at ease, audience too. I’m reminded of Mary Poppins and her spoonful of sugar. It’s not always appropriate to use humor, of course, but when I can, I do.

As important as creating a common experience is providing a unique experience. There are some things only I can deliver, and that’s what an audience or reader has come to get. Most people know what it’s like to trip and fall, but do they know how it feels during the middle of a live, professional performance? Do they know what happens when you go careening down a red dirt hillside in a canyon? Probably not! The details are what turned the occurrence into a precious memory, one you feel compelled to share. Adding simply one sentence to add dimension and color or orient the reader in a space they are trying to picture makes the whole story more rare, therefore more valuable.

To change a story from something pleasant—a nice way to pass five minutes—to something a reader can metabolize and use, I share the lump in my throat. In writing, we are taught to know and highlight “the stakes.” What is at risk in this story? Why should anyone stick around to see what happens? During live storytelling, I invite my emotions to the surface—both my recollection of the feelings I had during the original event and the feelings I have as a fellow audience member, someone examining what happened. Very often, the ten seconds that begin “looking back” or “now I know,” become the most important ten of my 300 behind the microphone—and my voice often cracks, even if just for a second. Past events, whether weighty or light-hearted, leave us with some drop of grief, gratitude, or (most likely) both. When we share our grief and gratitude, we inspire our readers and audiences to access their own.

For these secret ingredients to shine in my stories, I trim everything that buries them. Sometimes that means cutting a few good laughs to make room for the one great laugh. Other times, I only give details to the most crucial part of a story and cut all the other clever (to me) observations I wish I could include. The audience won’t know what they don’t hear, but they might remember one great line forever! Recently, I went back to editing my novel after a year of winning Moth StorySLAMs and was amazed by how much more easily I could “kill my darlings,” as Faulkner has encouraged us writers to do. For work to work, it must be made in service of the audience. Sure, they don’t know all I have to give—want to give—but hopefully they will be eager when I next approach the mic or publish another piece of writing. And that is a true win.